If you are a leasehold owner of a property and are in need of some extra space, the jump to a house may be a financial step too far especially if you plan to stay in the same area. Stamp duty alone will be a significant cost. The obvious alternative is to extend your property or a rear extension if you are on the ground floor or a loft conversion if you are on an upper floor.

The right to undertake this work essentially falls into one of two categories. One under which you follow a relatively straight forward process to obtain consent for the works from your freeholder and a second whereby you have to pay possible compensation. What follows is a basic guide to how you should approach this process.

Initial legal considerations

Life as a leaseholder is unfortunately, a little more complex than when you own a property in outright freehold possession. One of the first things you need to determine is do you have the right to undertake your works, or can your freeholder prohibit you from doing so. With a loft extension, this can often be as simple as you not owning the space itself. The same test is true with a rear extension, but in most instances the rear garden will already form part of the demise of your flat.

Even if you do own the relevant spaces, your lease can still prohibit you from undertaking works. You can do some investigation yourself, but you may wish to instruct either a surveyor or solicitor to review your lease to offer an opinion as to what the freeholder may and may not restrict.

Many leases contain the phrase “consent for alterations is not to be unreasonably withheld” however this needs to read in context to the lease as a whole, and any other restrictive covenants that may be present. Internal non-structural alterations may be permitted. Forming an opening in the external fabric of the building may not.

The answer may not be entirely clear cut, but either way, you will need to inform your freeholder of your proposed works. He will either insist on a license to alter or payment for the release of the covenant and/or the space that you do not own.

License to Alter.

If it is concluded that the freeholder cannot stop you from undertaking works, there is still due process to be followed. Most leases will require a leaseholder to obtain consent from their freeholder before making any alterations to their property. The formal consent called a Licence to Alter. The aim of the process is to ensure that the interests of the freeholder and other locally affected leaseholder is protected and is initiated by a solicitor drafting the documentation. Whether this is a solicitor instructed by the freeholder or yourself as a leaseholder is a matter for negotiation between the two of you as is the choice of surveyor. The surveyor’s role would include:

• Reviewing the draft license to ensure in respect to surveying related issues

• Scheduling the condition of any affected communal and external parts and adjoining flats that are affected

• A possible interim visit to view the works in progress (usually dependent on complexity and scope)

• A final visit to check off the schedule. Highlight and deal with any outstanding issues

Whilst the freeholder would expect all of their reasonable costs to be covered in this situation, they should certainly not profit from the exercise. This is in stark contrast to the route outlined below, where the freeholder can prohibit your works and enforce a restrictive covenant.

Development Valuation

One of the first things to point out in respect to this route is that the freeholder is under no legal obligation to be reasonable in all senses of the word. Whilst the process of the license is born out of the lease and the “unreasonably withheld” clause, there is no act of legislation that compels a freeholder to either sell an un-demised space or release a leaseholder from a restrictive covenant. The Leasehold, Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993 allows leaseholders to collectively enfranchise their building/block (the action is ultimately a forcible one), but that is very much an alternative consideration. If the freeholder wishes to reject your request or ask for a vastly inflated sum, there is no legal recourse outside of using this Act.

That said, there is well-established best practice methodology for what are often referred to as “development valuations” which in their most basic form, calculate the hypothetical profit that that would arise from the works of which 50% is paid to the freeholder.

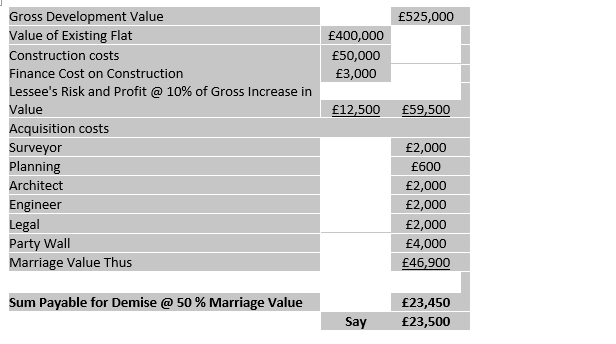

A chartered surveyor will need to value all of the relevant inputs, but a typical calculation would look something like this:

Following this, your surveyor may enter into negotiations with the freeholder’s surveyor, as the latter will be instructed to argue that the inputs result in a higher premium. In some rare instances, your freeholder may be happy for a singular joint expert be commissioned to produce a report, saving the cost, time and stress of a more adversarial approach. There are some good and fair freeholders out there, they are just normally few and far between!

Conclusion

The route that you will have to take as a leaseholder will be dictated but a combination of your lease terms and the stance of your freeholder. The License to Alter process is more of a box ticking exercise that should not be overly complex of adversarial. The Development Valuation route is becoming more widely known with the cast numbers of leaseholders converting their lofts but you will need strong and expert professional advice to see you through the process.